There are plenty of down-right creepy things that you may come across while traveling in Europe. And, at this time of year, we thought you might be interested in learning about some of the creepiest things we’ve seen when in Europe.

I am a sucker for things slightly weird and macabre, and when in Europe I am always on the look-out for an opportunity to get my “creepy fix”. While churches are, without question, the historical, cultural, architectural and spiritual centers of most every European community, they are also the place where I can usually find gruesome displays that invariably pique my interest. It is always amazing to me how many churches feature relics, corpses, or plain old bones. So, I pop  into almost every church I come upon…just in case. Here are a few examples of the treasures I have found while checking out churches in Europe.

into almost every church I come upon…just in case. Here are a few examples of the treasures I have found while checking out churches in Europe.

St. Catherine’s Head

Set in a reliquary in St Dominic Basilica in Siena, Italy, you can view the head of St. Catherine of Siena. The story is that she was in Rome when she died. When her fellow Sienans heard of her death, they wanted to transport her body back to Sienna. But the Vatican would have none of it. So, they stole her head and placed it in a sack to take back to Siena. When the Vatican authorities confronted the thieves, they opened the sack to find only rose petals. When the thieves got back to Siena, the head was magically reconstituted, so they put it on display. Nearby, you can also gaze upon one of her fingers, also encased in glass. And, it appears that her foot is on display in Venice.

St. Agnes Body

Also in Italy, I came upon a little church in Montepulciano where I saw St. Agnes’ corpse encased in a glass coffin. There was a mask over her face, so all you could see were her hands and feet, and her brown skin stretched tightly against the bone. Her hands were covered in rings. I have tried to discover the reason for all the rings, but have not been able to do so. Agnes of Montepulciano was canonized by Pope Benedict XIII in 1726. Her feast day is April 20.

Also in Italy, I came upon a little church in Montepulciano where I saw St. Agnes’ corpse encased in a glass coffin. There was a mask over her face, so all you could see were her hands and feet, and her brown skin stretched tightly against the bone. Her hands were covered in rings. I have tried to discover the reason for all the rings, but have not been able to do so. Agnes of Montepulciano was canonized by Pope Benedict XIII in 1726. Her feast day is April 20.

Terri Fogarty

More Creepy Europe Sights

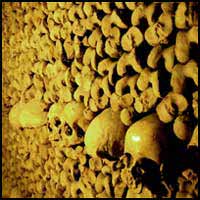

Paris Catacombs

Looking for something spooky to do in Paris this Halloween- or any old time? Well, you can’t beat one of the creepiest (and most fascinating) sights in the city, the Catacombes de Paris. The catacombs date back to the end of the 18th century. They were established because a nearby cemetery was found to be the origin of disease and infection to the local population. To reduce this risk, the bodies in the nearby cemetery were exhumed and placed underground. Today, visitors can tour the bone-lined caverns and tunnels of the old stone quarries.

Looking for something spooky to do in Paris this Halloween- or any old time? Well, you can’t beat one of the creepiest (and most fascinating) sights in the city, the Catacombes de Paris. The catacombs date back to the end of the 18th century. They were established because a nearby cemetery was found to be the origin of disease and infection to the local population. To reduce this risk, the bodies in the nearby cemetery were exhumed and placed underground. Today, visitors can tour the bone-lined caverns and tunnels of the old stone quarries.

Jen Westmoreland Bouchard

Hallstatt’s Beinhaus

600 human skulls serving as their own tombstones in one of Europe’s most picturesque towns? Sounds like it might be worth a stop. I was driving south from Salzburg through Austria’s Salzkammergut, one of Europe’s most fairlytale-esque areas, and it was a perfect day. Brilliant sunshine glittered upon the water and surrounding land, birds chirped as in a Disney movie, and the air smelled so dewy sweet I wished I only needed to breath in. Nothing but turquoise blue lakes, emerald green pastures, and soaring snow-capped mountains entered my view as I buzzed my rented Peugeot down the highway. And, the rhythmic sound of music beat within my head.

Feeling a need to balance out this cheeriness overload, I careened my little car down to Hallstatt, a tiny town nestled between sharply rising Alpine mountains and perched upon a glassy lake. A delightful town, I thought, how could anything be depressing here? That sentiment quickly faded when I entered Hallstatt’s Beinhaus (Bone House), a collection of 2,100 skulls and untold numbers of bones crammed into a tiny, dank chapel.

Feeling a need to balance out this cheeriness overload, I careened my little car down to Hallstatt, a tiny town nestled between sharply rising Alpine mountains and perched upon a glassy lake. A delightful town, I thought, how could anything be depressing here? That sentiment quickly faded when I entered Hallstatt’s Beinhaus (Bone House), a collection of 2,100 skulls and untold numbers of bones crammed into a tiny, dank chapel.

The chapel is adjacent to Hallstatt’s cemetery, and remains from the cemetery were moved into the chapel as space in the graveyard was depleted. Graves are now temporarily rented in this town, with rentals lasting about 10 years before the next unlucky tenant moves in. The remains of the previous tennants are, of course, moved to the chapel. In lieu of a tombstone, family and friends decorate the skulls of their loved ones with their name, year of death and decorations such as flowers or serpents. Since the 12th century this practice has worked for Hallstatt’s citizens, a sobering example of people adapting to their surroundings.

Standing in front of the skeletal remains, (which are not protected by glass or otherwise shielded from contact with visitors) one is faced with that rare opportunity to give those thoughts on mortality some momentary respect.

And, while walking back into the town – with waterfalls splashing at my feet and a nearby lake mirroring the sun – I found myself a little more able to appreciate the beauty around me. Plus, my cheeriness overload had been relieved.

Mike Coletta

Lenin’s Tomb

His corpse lies in darkness. He wears a black suit, thin tie and crisp dress shirt, as though he fell asleep, stiffly, in funeral clothes. A mustache and goatee wisp over ghostly-pale skin. But Vladimir Lenin died over 86 years ago; and his mummy, embalmed by generations of Russian scientists, still lies in state in Moscow. Visitors to the corpse pass from the bright, bustling Red Square – Moscow’s central political and cultural plaza – into the darkness of a tomb. Armed guards wear faces made of Russian winter: cold, hard, brutal. Forbidden actions include: photography, wearing hats, and putting hands in one’s pockets. The guards do not move. In the shadowy corridors, which wind sinuously through the dimly-lit tomb, they stand sentinel. Only a single hand gesture points us down the next hallway. The tomb seems to descend infinitely into the darkness. Then suddenly, there he is: pale skin glowing, eyes closed. A man dead for nearly a century, his mumified corpse is monthly dipped in a chemical bath to preserve its organs and skin. The Bolshevik leader’s body, as waxy white as the day he died, remains a macabre reminder of Russia’s Soviet past.

His corpse lies in darkness. He wears a black suit, thin tie and crisp dress shirt, as though he fell asleep, stiffly, in funeral clothes. A mustache and goatee wisp over ghostly-pale skin. But Vladimir Lenin died over 86 years ago; and his mummy, embalmed by generations of Russian scientists, still lies in state in Moscow. Visitors to the corpse pass from the bright, bustling Red Square – Moscow’s central political and cultural plaza – into the darkness of a tomb. Armed guards wear faces made of Russian winter: cold, hard, brutal. Forbidden actions include: photography, wearing hats, and putting hands in one’s pockets. The guards do not move. In the shadowy corridors, which wind sinuously through the dimly-lit tomb, they stand sentinel. Only a single hand gesture points us down the next hallway. The tomb seems to descend infinitely into the darkness. Then suddenly, there he is: pale skin glowing, eyes closed. A man dead for nearly a century, his mumified corpse is monthly dipped in a chemical bath to preserve its organs and skin. The Bolshevik leader’s body, as waxy white as the day he died, remains a macabre reminder of Russia’s Soviet past.

Caitlin Dwyer

Crypt of San Bernardino alle Ossa

It was dark inside San Bernardino alle Ossa. The church had been built in Milan in the 13th Century. The neighboring cemetery had run out of room to bury the city’s dead, and as a result, skeletons were dug up to make room for new bodies. These skeletons were the foundation of the church of San Bernardino alle Ossa.

It was dark inside San Bernardino alle Ossa. The church had been built in Milan in the 13th Century. The neighboring cemetery had run out of room to bury the city’s dead, and as a result, skeletons were dug up to make room for new bodies. These skeletons were the foundation of the church of San Bernardino alle Ossa.

The church was vacant when I visited, and there were no signs to help me find my way. Luckily, I was updating information for a guidebook that told me where to find the bones. I turned to my right to find the small passageway over which a sign read – Ossario –, which means bone room. I had to stoop to navigate the dark twists and turns of a stone walkway, finally ending in a chapel lit by candles. Hundreds of skulls peered down from the walls, all arranged in the form of two gigantic crosses. Bones artfully covered almost every inch of the chapel. I walked to the front to light a candle, and I heard the sorrowful laugh of an old woman. When they met mine, her eyes opened wide, just as a wind came up through the floor, the candles went out, and the moans of the dead filled my ears… Read more about Visiting Italy’s Crypts

Mattie Bamman

What creepy things have you seen in your travels to Europe? We’re dying to know…

Comments