Cluj, Romania is a city of many different faiths and historic communities, just like the region of Transylvania in which it sits. In another article, we’ve already looked at its two largest churches and the stories behind them. But in this article, we’ll explore some of the smaller churches and the congregations they serve. In this compact and culturally rich city, all of these beautiful and widely different churches are located within a few square miles.

The most prevalent Protestant denomination in Transylvania is the Reformed or Calvinist faith. The church in the southern part of the city center now belongs to the Calvinists, but was the site of some inter-denominational conflict in centuries past. Built in 1486-1516, it originally belonged to Franciscan monks. Townsfolk filled with Protestant zeal raided it in 1556 and trashed its sculptures and icons. The Franciscans relinquished the church and it was given to another Catholic group, the Jesuits, in 1579. Protestants struck again in 1603, ransacking the building and destroying the roof. In due course, the Jesuits said goodbye to the building and in 1622 it became what it is now: a Calvinist church with a Hungarian-speaking congregation.

The most prevalent Protestant denomination in Transylvania is the Reformed or Calvinist faith. The church in the southern part of the city center now belongs to the Calvinists, but was the site of some inter-denominational conflict in centuries past. Built in 1486-1516, it originally belonged to Franciscan monks. Townsfolk filled with Protestant zeal raided it in 1556 and trashed its sculptures and icons. The Franciscans relinquished the church and it was given to another Catholic group, the Jesuits, in 1579. Protestants struck again in 1603, ransacking the building and destroying the roof. In due course, the Jesuits said goodbye to the building and in 1622 it became what it is now: a Calvinist church with a Hungarian-speaking congregation.

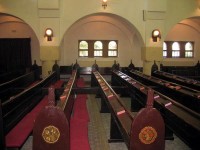

There followed a series of 17th century renovations, including new vaulting and a pulpit made from limestone and alabaster, creating an interior that remains largely unchanged to this day – somewhat sparse, and still with a Gothic look. The simple wooden pews date from that time. However, the ornate organ housing is from 1765, as it was not until then that the Reformed congregation countenanced organ playing. The church’s single nave is extremely broad.

The statue outside the church’s entrance, showing St. George killing a dragon, is a miniature replica of one that still stands in the Czech capital Prague, having been created for that city in 1373 by a pair of Cluj-based sculpting brothers.

The statue outside the church’s entrance, showing St. George killing a dragon, is a miniature replica of one that still stands in the Czech capital Prague, having been created for that city in 1373 by a pair of Cluj-based sculpting brothers.

Slightly to the west of the central square in Cluj, named Piata Unirii, stands the Greek Catholic church, which, though small, is a relatively important seat for this dwindling denomination. Greek Catholicism was popular among Transylvanian Romanians in the 18th century because it allowed them to be in full communion with the Catholicism of their Austrian rulers while keeping Orthodox rites. Accordingly, this church’s interior is a weird hybrid. Like an Orthodox church, it has an iconostasis, icons painted on the walls, and no statues. But there is a Catholic flavor to its pale colors – the Stations of the Cross paintings hanging on the walls, and the fact that there is a pulpit. A side chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary, though lacking a statue, in other respects resembles something from a Catholic church, including votive tablets hung on the wall by parishioners.

To the south of Piata Unirii is a Roman Catholic church displaying the Baroque style typical of the 18th century, when the Austrians sent Jesuits around Transylvania to revive Catholicism. In fact, this was the first church the Jesuits built in the region during that counter-Reformation. It has a splendid, highly ornamented interior, with lots of gold.

A real curiosity is the “Cock Church” built in 1912-13 by Karoly Kos, an architect influenced by Transylvanian Hungarian peasant art. A 20 minute stroll west from the city center, this salmon-pink edifice is named for the rooster designs on the top of its tower and on the interior lampshades. The church offers a modern twist on village architecture, with stylized folk motifs punctuating the simple dark wood planks of its chunky but elegant interior.

A real curiosity is the “Cock Church” built in 1912-13 by Karoly Kos, an architect influenced by Transylvanian Hungarian peasant art. A 20 minute stroll west from the city center, this salmon-pink edifice is named for the rooster designs on the top of its tower and on the interior lampshades. The church offers a modern twist on village architecture, with stylized folk motifs punctuating the simple dark wood planks of its chunky but elegant interior.

A faith strongly associated with Transylvania’s Hungarian community is observed in the Unitarian church, built in 1792-96. This faith – in which there is only one God rather than a  Trinity – was mostly adopted by ordinary folk, because aristocrats, as part of their duties, sometimes needed to swear on the cross. In keeping with the Unitarian ethos, this church contains no pictures. Its broad, sweeping, single-nave interior, topped by a low arched ceiling, is plain and simple. The walls are painted a uniform pale yellow and punctuated with big windows. During services, the priest likes to stand facing the crowd rather than delivering his words from a pulpit.

Trinity – was mostly adopted by ordinary folk, because aristocrats, as part of their duties, sometimes needed to swear on the cross. In keeping with the Unitarian ethos, this church contains no pictures. Its broad, sweeping, single-nave interior, topped by a low arched ceiling, is plain and simple. The walls are painted a uniform pale yellow and punctuated with big windows. During services, the priest likes to stand facing the crowd rather than delivering his words from a pulpit.

A stone’s throw west is the Lutheran church, which stands on the northeast corner of the square named Piata Unirii. The word “Pietati” is written on the front facade, meaning “To Piety” in Latin. Inside, this church proves to be another big, arched, elegantly simple single-nave, although it has more adornment than the Unitarian one. The columns that support the expansive white interior are touched up with gold paint on their bosses. The north wall contains a couple of small epitaphs to local officials from the 17th and 18th centuries. This church was constructed in 1816-1829 in a style that is a fusion of Baroque and Neo-Classical. Its congregation mostly consists of ethnic Hungarians, and services are held in their language.

Travelers to Cluj who want to know its history, culture, and people, need only visit its many religiously significant churches.

Comments